How to describe it? How to convey how it feels being in this strange, wondrous part of the planet, and do it justice? Impossible. I once asked my neighbours’ daughter, Katie Brailsford, who teaches overseas and has visited many distant places, which was her favourite, and she said “Mongolia.” Now I know why.

Vast is the word a fellow traveler, Susan Blayney, started with. She’d been banding birds for two weeks in a remote creek valley nine hours north of Ulaanbaatar when the rest of us arrived for the “birding tour” part of our expedition—nine Canadians setting out in land cruisers to explore “Middle Mongolia.” Which could have been Tolkien’s “Middle Earth,” it was so beautiful and unfamiliar.

The first thing you notice is the lack of trees. Their total absence, except where planted and protected from grazing animals in towns and villages. With the massive wall of Himalayas to the south, blocking off India’s monsoons, the Mongolian plateau relies on moisture carried in on winds from the Arctic, enough to water trees on north-facing slopes in the steppes, but leaving south-facing ones parched and bare.

The farther south you go, the drier it becomes, and the Gobi itself includes 21 different habitat types, someone told me. The complex distribution of remaining vegetation—shrubs, sedges, grasses, wildflowers—depends on how much rain arrives where, and how much snow blows in from Siberia across this “high cold desert” tucked between Russia and China.

But without trees muffling the view you get to see the land itself, almost enough to make you cry, it’s so stunning. Sweeping lines and curving contours of ancient mountains scoured and sculpted by winds for 66 million years. Once covered by inland lakes, according to my driver, who knew a tiny bit more English than I knew Mongolian. So I couldn’t ask all the questions buzzing in my head, just had to gaze in wonder and absorb the spectacular scenery that surrounded us as we made our way south into the Gobi, Mongolian for “waterless place.”

Another thing you notice is the strange lack of fences. Total lack. You drive for a day, a week, across the countryside and there’s not a single strand of barbed wire stopping you, saying “this is mine; keep off.” Mongolian culture doesn’t seem to include the square-cornered grid pattern that carves the rest of the world into boxes, instead remaining fluid and free. So horses can gallop, and goats, sheep, cattle, camels and yaks graze at will, sometimes tended by herders on horseback or motorcycles, sometimes wandering on their own. Even Mongolian homes, those circular, lightweight, wind-resistant “gers,” or yurts, are movable.

Also strange to newcomers is the lack of roads. Where asphalt ends, vehicles simply take off across the countryside, following dirt tracks or making up routes as they go. Our skilled and fearless drivers, owners of the powerful land cruisers carrying us, our gear and camping equipment, took us through rock-strewn gorges, along dry creekbeds, across shifting dunes, up steep slopes and down again, some truly gut-tightening terrain. For nearly two weeks we didn’t see pavement, driving on chalk and hard pan sediments worn down from ridges of eroding bedrock perpetually surrounding us. Rims of hills and mountains continually in view, even in the congested, semi-chaotic capital, where half of Mongolia’s three million citizens live.

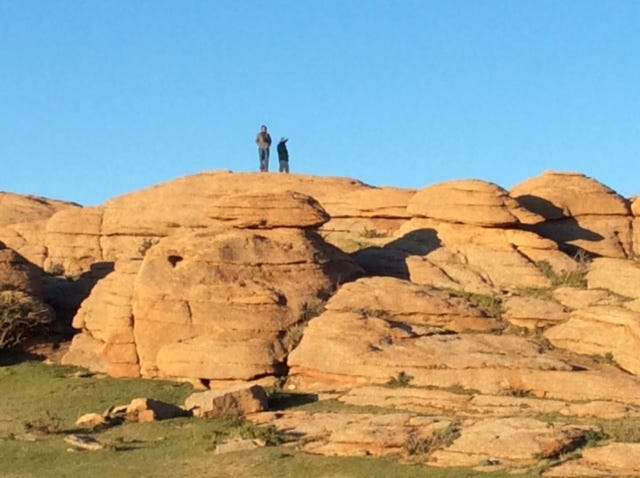

Always eye-catching, always welcoming, that rolling landscape. Every time we camped I was amazed, overwhelmed even, by how Tumen, our trusty expedition guide, would find a dramatic site for us to pitch our tents, eat supper, watch the stars come out. Places with cliffs and jagged heaps of rocks to walk among at dawn, watching for birds before breakfast. Some of the most spectacular campsites I’ve ever come across. Even in Australia. Even in Arizona.

They call Mongolia “land of eternal blue skies,” a result of all that dry air. I loved how fair-weather clouds would cast shadows on the land below, painting the tan canvas of the Gobi with splotches of black and grey. We did experience a storm or two, one sending our support team scurrying to take down tents in stinging winds so we could retreat to a nearby village and hotel. Then shake sand our of our packs and sleeping bags for days to come.

In our unforgettable two-weeks-plus together my driver, Omnogope, taught me a few words in Mongolian, including thank you, good morning, lake, mountain, beautiful, wonderful. And the words for a single horse and for herd. Obviously important to him, as he owns a hundred mares, 21 new foals this spring, three stallions, and some cattle and sheep, tended by his in-laws when he’s off driving tourists around the country. He also races horses—fearlessly, judging from his driving. And he loves music, singing along to the CD tracks he often played as we travelled. Mongolian music, sometimes haunting and feeling-full, sometimes charged with the energetic rhythm of hoofbeats, made a great sound track for the passing landscape.

How to share the feeling, the beauty, the essence of Mongolia? I was right—impossible. A thousand pictures don’t do it justice. But I’m moved to tears yet again as I remember, with deepest gratitude, how lucky I was to visit this exquisite, very special part of the planet.

All my life I’ve wanted to go there. Now I know why.

For Tumen’s EcoTour website visit: www.wildlifemongolia.com

I get the feel of the land and this amazing country that I, too, have wanted to visit. Now even more after this reading. I can just imagine you there glowing over everything and everybody - spreading blessings and joy just as the storm spread sand! Wonderful descriptions, my friend. Thanks for sharing your journey!